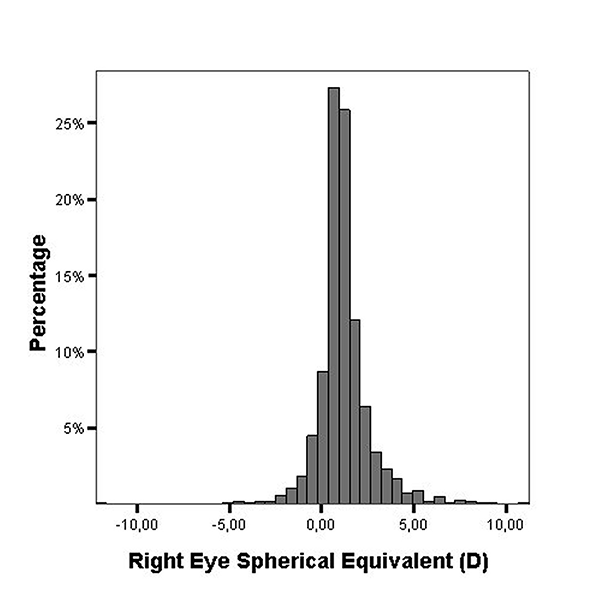

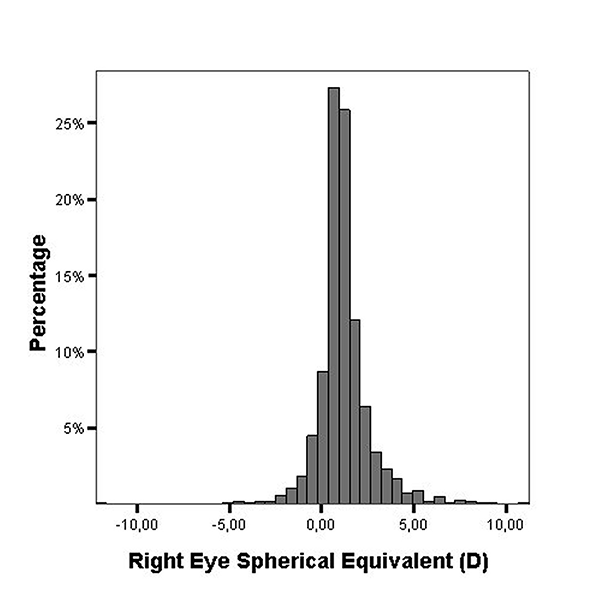

Figure 1. Distribution of the spherical equivalent of the auto refracted right eyes.

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Low prevalence of myopia in children from the Andean region in Ecuador

Luis Zemana, Andrea Molinarib, Alejandra Balsac, Mario Angid, Santa Heedee, Rafael Iribarrenf

a Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital de Clínicas, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

b Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Metropolitano, Quito, Ecuador.

c Augen Ophthalmologists, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

d Department of Neurosciences, University of Padua, Padua, Italy.

e University Eye Clinic, Hamburg, Germany.

f Drs. Iribarren Eye Consultants, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Received: July 2nd, 2021.

Accepted: September 11st, 2021

Oftalmol Clin Exp (ISSN 1851-2658)

2021; 14(4): 202-209.

This submission has not been published previously and it is not simultaneously being considered for any other publication.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have any proprietary interests or conflicts of interest related to this submission.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part with funds from EC Alfa Project ARL 2.039 (6) and from Progetto CEI 022/99 “Formazione di Personale per la Diagnosi e Correzione dell’Handicap Visivo in Ecuador”. Authors wish to thank Dr. Leon Ellwein (National Eye Institute, USA) for his help with the Chilean data in table 2.

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Conflict of interest

Luis Zeman, Andrea Molinari, Mario Angi, Santa Heede, Alejandra Balsa and Rafael Iribarren declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Financial support

None for all authors.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ABSTRACT

Purpose: The prevalence of myopia has been increasing in young people in East and South East Asian urban environments. It has been predicted that by 2050 half of the world population will be myopic, and of those, 10% will suffer from high myopia. The prevalence of myopia in Latin America, which holds 1/10th of the world population, has been scarcely studied. The present study reports on the prevalence of myopia among children living in Ecuador.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional population-based study conducted in 2001. The sample consisted of schoolchildren from the Andean region in Ecuador. The ocular examination was performed at schools by trained ophthalmologists. Children who did not reach a visual acuity of 10/10 in both eyes were submitted for cycloplegic refraction. Automated cycloplegic refractive error measurement and subjective refraction were performed. Myopia was considered as spherical equivalent refractive error <-0.50 dioptres.

Results: The study included 6,143 schoolchildren aged 8.54 ± 2.75 years. There was an extremely low prevalence of myopia (2.69%) and high myopia (0.16%) in the studied population.

Conclusion: Low prevalence of myopia and very low prevalence high myopia were found among children living in the Ecuadorean Andean region compared to Asian urban environments.

Key words: myopia, prevalence, Ecuador, Latin America.

Baja prevalencia de miopía en niños de la región andina en Ecuador

RESUMEN

Objetivos: La prevalencia de miopía ha aumentado en los jóvenes de los centros urbanos del este y el sudeste asiático. Se ha predicho que para el año 2050 la mitad de la humanidad será miope y que el 10% padecerá miopía alta. Existe poca evidencia acerca de la prevalencia de la miopía en América Latina, que representa el 10% de la población mundial. El presente estudio informa sobre la prevalencia de errores de refracción en los escolares de la región andina de Ecuador.

Materiales y métodos: Se realizó un estudio poblacional transversal en el año 2001 en dos escuelas de Quito e Ibarra, Ecuador. Se realizó refracción bajo cicloplejía (ciclopentolato 1%) con autorrefractómetro. Se tomó al equivalente esférico ≤ -0.50 como punto de corte para definir miopía y ≤ -5.00 para miopía alta.

Resultados: Se estudiaron 6.143 escolares de 8,54 ± 2,75 años con un rango de 5 a 16 años. La prevalencia de miopía (2,69%) y de miopía alta (0,16%) fue muy baja en la población estudiada.

Conclusión: Se observó una baja prevalencia de miopía entre los niños que viven en la región andina ecuatoriana en comparación con otros estudios poblacionales, especialmente de los grandes centros urbanos asiáticos.

Palabras clave: miopía, prevalencia, Ecuador, America Latina.

Baixa prevalência de miopia em crianças da região andina do Equador

RESUMO

Objetivos: A prevalência de miopia aumentou o número de jovens em centros urbanos não no leste e sudeste da Ásia. Prevê-se que em 2050 a meta da humanidade seja míope e que 10% sofra de alta miopia. Existem poucas evidências sobre a prevalência da miopia na América Latina, que representa 10% da população mundial. Este estudo informa sobre à prevalência de erros refrativos em escolares da região andina do Equador.

Materiais e métodos: Um estudo transversal da população foi realizado em 2001 em duas escolas em Quito e Ibarra, Equador. A refração sob cicloplegia (ciclopentolato 1%) foi realizada com autorefratômetro. O equivalente esférico ≤ -0,50 foi considerado como ponto de corte para definir miopia e ≤ -5,00 para miopia alta.

Resultados: Foram estudados 6.143 escolares com idade entre 8,54 ± 2,75 anos e variação de 5 a 16 anos. A prevalência de miopia (2,69%) e alta miopia (0,16%) foi muito baixa na população estudada.

Conclusão: Uma baixa prevalência de miopia foi observada em crianças que vivem na região andina do Equador em comparação com outros estudos populacionais, especialmente em grandes centros urbanos asiáticos.

Palavras-chave: miopia, prevalência, Equador, América Latina.

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of myopia has been increasing in recent generations of young people from different regions of the world, affecting especially younger generations from East and South-East Asian urban environments. Based on this epidemic of myopia, some researchers have proposed that by 2050 half of the world population might be myopic and about 10% will suffer from high myopia1-3. Considering the deleterious consequences of visual impairment in late adulthood produced by high myopia, especially myopic maculopathy, this produces great concern4. Latin America has 1/10th of the world population, involving an affluent mixed population where people coming from all parts of the world have settled and mixed with the aboriginal populations that have lived for more than 10,000 years in the continent, after migrating from East Asia across Alaska5. There are few epidemiological studies of refractive error in children in Latin America6-9. Because of that the objective of the present study was to evaluate and show that in the Andean region of Ecuador, where the Incas developed their culture, and people are now mainly a mixture of native Americans with people of European descendant, there is a historically very low prevalence of myopia and high myopia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design, ethics and participants

This was a cross-sectional population-based study that involved schoolchildren aged 4 to 16-year-old living in two cities (Quito and Ibarra) in the Andean region of Ecuador. Methods were presented in a previous analysis of this sample10. In brief, all children attending eligible public schools in Carapungo (a neighborhood in the city of Quito) and in a nearby city called Ibarra, were examined in 200210. These two locations include a mestizo Andean population descendant from the Inca Empire which contacted Europeans about 500 years ago. In Quito 2,286 children were involved and 3,857 in Ibarra. There were no differences in age or gender in the two locations, so both data are presented together10. This screening was approved by the Diócesis of Ibarra Ethics Committee (Ibarra, Ecuador), and followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Agreement was obtained from the directors of the schools in which the study was conducted. The teachers sent parents a formal communication about the visual screening two weeks before the study. Children gave verbal consent for the ocular examination at the time of the study. All data were treated confidentially.

Settings and procedures

The ocular examination took place at the school buildings. The children were examined by a team of ophthalmologists who first tested visual acuity with the HOTV test at 3 meters distance (Precision Vision, USA). The threshold for normal visual acuity was established at 10/10 (at least 4 of 5 letters in the line) and when a child did not reach this visual acuity in either eye, the child was referred for cycloplegic refraction and fundus exam. The cycloplegic refraction was performed after instilling two drops of cyclopentolate 1% into the inferior fornix twice, 10 min apart. A third drop was instilled if inadequate dilation was noted. The autorefraction was performed 40 min after instillation of the first drop with an autorefractometer (Canon R-50, Canon). The mean of five consecutive measurements was recorded. One month later, trained optometrists performed a subjective refraction with this cycloplegic information. Spectacles were prescribed and provided by technical personnel at a subsidized cost of 4 US dollars.

Main outcomes and statistical evaluation

The spherical equivalent refraction was calculated as the sphere + ½ the cylinder value of the cycloplegic autorefraction. Refractive data are presented for the right eyes, because data obtained in the left eye were similar (r=0.896, p<0.001). For reporting prevalence of refractive error, the present study followed the protocol used in the Refractive Error Studies in Children and the recommendations of the International Myopia Institute: myopia was considered as spherical equivalent refractive error ≤ -0.50 diopters11-12. For the purpose of this study astigmatism was considered as that ≤ -2.00 diopters (but other cut points are presented for comparison with other studies). Parametric values are expressed as mean, standard deviations and range. The data were recorded in an Excel spreadsheet and converted to SPSS database for the analysis (SPSS version 15, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

The sample consisted of 6,143 children aged 8.54 ± 2.75 years, range 5 to 16 years of whom 2,775 (45.2%) were female. The mean uncorrected visual acuity in decimal notation was 0.89 ± 0.20 for the right eyes. The relative percentages of each visual acuity level are presented in Table 1. There were 1,702 (27.7%) children in the sample who did not reach the 10/10 cut off for uncorrected visual acuity in the right eyes. In this study 2,436 (39.6%) children were examined with cycloplegia, including all children with at least one eye which did not reach 10/10 visual acuity. The mean refractive error of these children was similar for both eyes (r = 0.86, p < 0.001) and its distribution can be seen in Figure 1. The mean refractive error was mildly hyperopic for the refracted right eyes (spherical equivalent = +1.19 ± 1.53 diopters).

Table 1. Relative percentages of visual acuity in decimals.

VA |

n= |

% |

0,05 |

12 |

0.2 |

0,10 |

11 |

0.2 |

0,13 |

14 |

0.2 |

0,16 |

29 |

0.5 |

0,20 |

30 |

0.5 |

0,25 |

84 |

1.4 |

0,32 |

96 |

1.6 |

0,40 |

103 |

1.7 |

0,50 |

170 |

2.8 |

0,63 |

270 |

4.4 |

0,80 |

883 |

14.4 |

1,00 |

4441 |

72.3 |

Figure 1. Distribution of the spherical equivalent of the auto refracted right eyes.

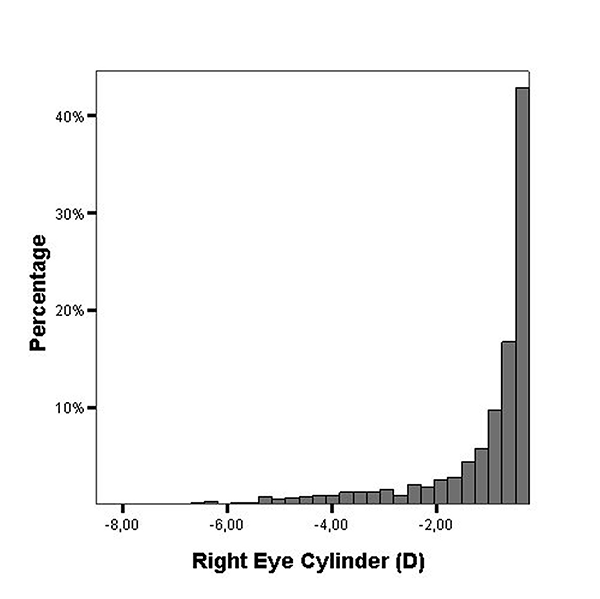

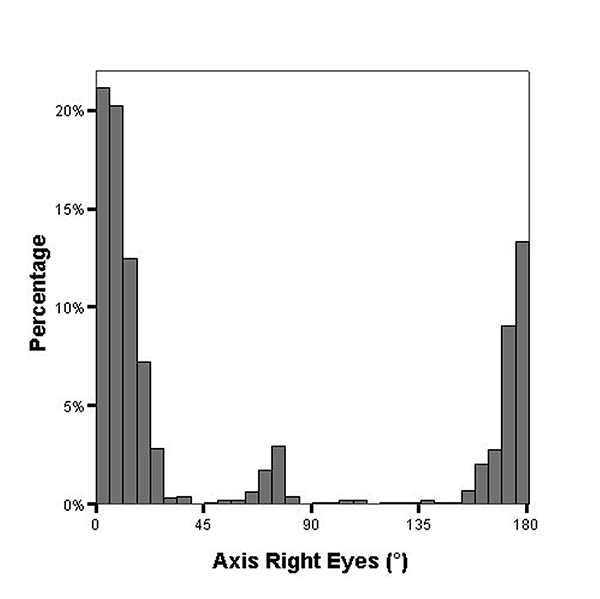

There were 165 subjects (2.69% of the whole sample) with myopic spherical equivalent ≤ -0.50 diopters (limit -12.25 diopters). There were 436 (7.09%) subjects with refractive cylinder ≤ -2.00 diopters (limit -8.50 diopters), 984 (16.02%) with cylinder ≤ -1.00 diopters and 1391 (22.64%) cylinder ≤ -0.75 diopters. Figure 2 shows the distribution of refractive cylinder and Figure 3 the distribution of the axis of these cylinders, which were mainly with-the-rule.

Figure 2. Distribution of the cylinder of right eyes.

Figure 3. Distribution of the axis of the cylinder in right eyes.

The high prevalence of high simple myopic astigmatism (≤ -2.00 diopters) made some subjects look like biased myopes with not true negative spherical equivalent (for example a -2.00 diopters simple myopic astigmatism classified as a -1.00 diopter spherical equivalent myopic subject). Thus, there were only 80 (1.30%) children with spherical component ≤ than -0.50 diopters (true myopes compared to 2.69% of myopic spherical equivalent). There were only ten subjects (10/6143; 0.16%) with high myopia ≤ -5.00 diopters of spherical equivalent in the right eye. There were 318 subjects with anisometropia of 1 diopter or more in the whole sample (5.17%).

DISCUSSION

In this school based cross-sectional study on the prevalence of refractive errors, the frequency of myopia is exceptionally low (2.69%) with virtually no high myopia (0.16%). The children included in this study belong to a mestizo population according to recent genetic studies in the zone13. Mestizo populations have a differentiated Amerindian genetic background, consistent with a mainly local native ancestry13.

These children live in the Andes Mountain Range, over a plateau surrounded by high mountains in two nearby urban environments (Quito, at 2.850 mts, and in Ibarra at 2.215 mts over the sea level). Quito, with around two million residents registered in 2010 has a population density of 5,401 inhabitants per square kilometer and Ibarra with 131,856 inhabitants has a population density 3,216 inhabitants per square kilometer (Hong Kong 6,300, Singapore 7,843, and Beijing 1,322). Ecuadorean children spent 4 hours a day at public schools and probably many more hours a day outdoors. At the time of the study (2001) they had no access to cell phones and very limited access to computers or video games. This study was performed nearly 20 years ago when the link between myopia and outdoor exposure was not yet discovered and therefore not investigated. Nowadays some changes in habits may have occurred, especially after the massification of cell phones and computers, so similar studies performed now, might bring up different results. In this context, the prevalence of spherical myopia is exceptionally low, even lower than in Nepal, a country with low literacy and high outdoor exposure where studied children were rural village dwellers14. This fact suggests that in children living in Ecuadorean suburban environments, perhaps similarly to what happens in great part of the cities in the underdeveloped world, there is no epidemic of myopia (Table 2). This should be considered not only for future perspectives, but also to study how living environment can influence refractive errors. Another factor to be considered is the extremely bright sunlight exposure that these children were subjected to. Due to the thin atmosphere found in the high altitude of Quito and Ibarra and the location near the equatorial line, the light exposure is more intense in this part of the world15.

The epidemic of myopia was first described in a population of Alaskan aboriginals, in whom the prevalence of myopia in those born before 1940 was 3%, and increased to 35-65% both in inuit and aboriginal children who were born between 1950 and 196016. Another epidemic was described in Singapore where the prevalence increased fivefold in military conscripts from 1980 to 200017. These changes were unexplained until the association between myopia and academic achievement or lack of outdoor exposure was discovered in recent years1. It would be interesting to measure academic achievement and outdoor exposure in Ecuadorean children in future similar studies to determine how much time outdoors is needed to achieve the low prevalence of myopia of this region (Table 2).

Table 2. Prevalence of myopia in different Latin American studies in children.

Author |

Location |

n= |

Age (years) |

Publication |

Myopia |

Maul6 |

Chile |

701 |

14-15 |

2000 |

8.86% |

Lira8 |

Campiñas (Br) |

266 |

12 |

2014 |

6.39% |

Schimiti22 |

Ibipora (Br) |

13471 |

6-15 |

2001 |

5.20% |

Salomao9 |

Sao Pablo (Br) |

2441 |

11-14 |

2008 |

4.56% |

Zeman23 |

Salta (Arg) |

1852 |

5-15 |

2021 |

3.61% |

Magnetto |

Marcos Juarez (Arg) |

283 |

12 |

in preparation |

3.53% |

Thorn7 |

Amazon (Br) |

441 |

12-59 |

2005 |

2.30% |

Zeman |

Ecuador |

1594 |

5-16 |

present study |

1.44% |

Carter24 |

Paraguay |

168 |

5-16 |

2013 |

1.40% |

Signes-Soler25 |

Paraguay |

1466 |

3-22 |

2017 |

0.50% |

Concerning the high prevalence of high astigmatism in this sample, it is interesting to note that our methods avoided classifying as mild myopes those with simple myopic astigmatism, which have myopic spherical equivalent. Even in case that those were included, the prevalence of myopic spherical equivalent would be extremely low, under 4% in the present study. The possible genetic background of the noticeable prevalence of high astigmatism in this study is beyond the scope of this paper and has been described thoroughly in a companion paper in preparation with similar data from Salta, Argentina. Noteworthy, we can state that this high prevalence of with-the-rule high astigmatism is probably genetic in nature, and related to Andean populations across the Americas, like those of Chilean children6 or Zuni and Navajo aboriginals18 which show high proportion of high astigmatism as Chinese children from East Asian environments19-20. Interestingly, Andean, Zuni and Navajo societies have upheld some degree of stability in their genetic background due to inbreeding, a fact which is associated with a high prevalence of genetic diseases18.

The cut point of 10/10 visual acuity used in the present study for screening myopia is very conservative as Leone et al. in the Sydney Myopia Study have shown that a cut point of 7/10 could equally serve to detect significant myopia21. Therefore, we believe that no child with myopia may have gone undetected in this study. Another strength of our study is that it was school-based, and given there is no discrimination for refractive errors in Ecuador at school entrance, high myopes were probably not undetected as well. Of interest, high myopia (over -5.00 diopters) in school aged children of low prevalence areas might probably be syndromic or genetic in nature, and was extremely rare in this studied sample. We do not report on hyperopia prevalence in this study because low hyperopes can accommodate for 10/10 uncorrected visual acuity and would be missed by our methods. Even in that case, the mean refractive error of children in whom cycloplegic refraction was performed was mildly hyperopic (around +1.00 D), showing that this seems to be the endpoint refractive development during childhood in a population with low prevalence of myopia.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, an exceptionally low prevalence of myopia or high myopia is reported historically for school-aged children in the Andean region of Ecuador, descendants of native Americans, evaluated in 2002. This might be explained by the genetic background, but especially by the environmental factors determined by the possibly limited near work and significant time spent outdoors under the bright sun of the Ecuadorian region. These children have also a significant prevalence of high astigmatism as other Andean children, which may probably be genetic in nature. The study of living habits of these populations, namely academic achievement, housing, outdoors exposure and spare time activities could contribute to the understanding of the myopia epidemics in developed urban environments in other parts of the world. Thus, future studies in this region should include the evaluation of myopia risk factors. Indeed this historical prevalence gathered 20 years ago could serve for the basis of future studies showing the trends in refractive error prevalence to see if Ecuador is developing the same epidemic of myopia as other parts of the world. In fact, little has changed in these 20 years with urbanization and academic performance of children in the zone, so it would be very interesting to replicate the study with questionnaires of outdoor exposure and reading habits.

REFERENCES

1. Morgan IG, French AN, Ashby RS et al. The epidemics of myopia: aetiology and prevention. Prog Retin Eye Res 2018; 62: 134-149.

2. Holden B, Sankaridurg P, Smith E et al. Myopia, an underrated global challenge to vision: where the current data takes us on myopia control. Eye (Lond) 2014; 28: 142-146.

3. Holden BA, Fricke TR, Wilson DA et al. Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology 2016; 123: 1036-1042.

4. Wong TY, Ferreira A, Hughes R et al. Epidemiology and disease burden of pathologic myopia and myopic choroidal neovascularization: an evidence-based systematic review. Am J Ophthalmol 2014; 157: 9-25.e12.

5. Cavalli-Sforza LL, Feldman MW. The application of molecular genetic approaches to the study of human evolution. Nat Genet 2003; 33 Suppl: 266-275.

6. Maul E, Barroso S, Munoz SR et al. Refractive error study in children: results from La Florida, Chile. Am J Ophthalmol 2000; 129: 445-454.

7. Thorn F, Cruz AAV, Machado AJ, Carvalho RAC. Refractive status of indigenous people in the northwestern Amazon region of Brazil. Optom Vis Sci 2005; 82: 267-272.

8. Lira RPC, Santo IFE, Astur GLV et al. Refractive error in school children in Campinas, Brazil. Arq Bras Oftalmol 2014; 77: 203-204.

9. Salomão SR, Cinoto RW, Berezovsky A et al. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment in low-middle income school children in São Paulo, Brazil. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008; 49: 4308-4313.

10. Virgili G, Angi M, Heede S et al. PowerRefractor versus Canon R-50 autorefraction to assess refractive error in children: a community-based study in Ecuador. Optom Vis Sci 2007; 84: 144-148.

11. Negrel AD, Maul E, Pokharel GP et al. Refractive error study in children: sampling and measurement methods for a multi-country survey. Am J Ophthalmol 2000; 129: 421-426.

12. Flitcroft DI, He M, Jonas JB et al. IMI: defining and classifying myopia: a proposed set of standards for clinical and epidemiologic studies. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2019; 60: M20-M30.

13. Wang S, Ray N, Rojas W et al. Geographic patterns of genome admixture in Latin American mestizos. PLoS Genet 2008; 4: e1000037.

14. Pokharel GP, Negrel AD, Munoz SR, Ellwein LB. refractive error study in children: results from Mechi zone, Nepal. Am J Ophthalmol 2000; 129: 436-444.

15. Parra R, Cadena E, Flores C. Maximum UV index records (2010-2014) in Quito (Ecuador) and its trend inferred from remote sensing data (1979–2018). Atmosphere 2019;10: 787-804.

16. Morgan RW, Munro M. Refractive problems in Northern natives. Can J Ophthalmol 1973; 8: 226-228.

17. Saw SM, Wu HM, Seet B et al. Academic achievement, close up work parameters, and myopia in Singapore military conscripts. Br J Ophthalmol 2001; 85: 855-860.

18. Mohindra I, Nagaraj S. Astigmatism in Zuni and Navajo indians. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1977; 54: 121-124.

19. Tong L, Saw SM, Carkeet A et al. Prevalence rates and epidemiological risk factors for astigmatism in Singapore school children. Optom Vis Sci 2002; 79: 606-613.

20. Yam JC, Tang SM, Kam KW et al. High prevalence of myopia in children and their parents in Hong Kong Chinese population: the Hong Kong Children Eye Study. Acta Ophthalmol 2020; 98: e639-e648.

21. Leone JF, Mitchell P, Morgan IG et al. Use of visual acuity to screen for significant refractive errors in adolescents: is it reliable? Arch Ophthalmol 2010; 128: 894-899.

22. Schimiti RB, Costa VP, Gregui MJF et al. Prevalence of refractive errors and ocular disorders in preschool and schoolchildren of Ibiporã-PR, Brazil (1989 to 1996). Arq Bras Oftalmol 2001; 64: 379-384.

23. Zeman L, Danza RD, Fejerman L, Iribarren R. Prevalence of high astigmatism in Salta province, Argentina. Oftalmol Clin Exp 2021;14: 162-170.

24. Carter MJ, Lansingh VC, Schacht G et al. Visual acuity and refraction by age for children of three different ethnic groups in Paraguay. Arq Bras Oftalmol 2013; 76: 94-97.

25. Signes-Soler I, Hernández-Verdejo JL, Estrella Lumeras MA et al. Refractive error study in young subjects: results from a rural area in Paraguay. Int J Ophthalmol 2017; 10: 467-472.